These chilling words echoed in the mind of

the young man as tears rolled down his face. Just a few hours earlier he had

felt the tremendous excitement and satisfaction that one feels when realizing

the fulfillment of a lifelong dream, one that was made all the more important

by the fact that he was following in his beloved father’s footsteps. In no time

at all it seemed as if the dream had become a nightmare, one he was sure to re-live

over and over in his mind, perhaps for the rest of his life. Being only 17

years of age, it was understandably not something that young Dick Steinborn was

looking forward to.

The Strength of My Father

Born the son of legendary strongman, professional

wrestler and promoter Henry “Milo” Steinborn, Dick had loved wrestling ever

since he could remember and became quite adept at it, receiving instruction

from his father and also many of the professional wrestlers who frequented the

basement gym of his family’s home during their time living in New York

“My dad had a stake in the New York Queens ,

New York New York

Dick took to wrestling like a fish to

water, just as he did to almost everything he ever tried, including the 17

different sports he would involve himself with at one time or another during

his life. “My dad always said, ‘Dickie can never keep still, he’s always moving.’”

At one point Dick Steinborn was diagnosed as having Attention Deficit Disorder,

and while it was difficult at times to focus his attention, whatever did catch

his attention was something he typically excelled at. It was no different with

wrestling.

He and his brother Henry excelled in

amateur wrestling while attending Trinity

High School in New

York , enough so that the coach from Columbia University

Milo Steinborn, whom Lou Thesz called “The

strongest man I ever wrestled,” was admired greatly by Dick for both his

accomplishments in the ring and his character as a man. “Dad was the Babe Ruth

of the sports world for a few years,” Dick would say. The training Milo provided his son in the weight room and on the mat

made Dick’s body strong and well prepared for the physical rigors of life in

the ring, but the mental preparation would prove to have even greater value to

Dick both in the ring and out of it. “I owe him everything I have,” his son

said with appreciation. “Not just in a physical sense but also my training of

mind.”

Still a few months shy of his 18th

birthday, Dick was unable to obtain a license to wrestle as a professional in New York , but to his delight, he was able to receive both

a professional wrestler’s license and a booking in the state of Maryland Astoria , Queens to make the 175 mile trek to Baltimore

On that special night on July 24, 1951,

for Dick, the noise of the crowd was near-deafening and the atmosphere was electric,

and despite it being his very first pro match, the match went smoothly. Approaching

the finish of the match, Dick escaped from a headlock that was applied by his

opponent Les Ruffin, by whipping him into the ropes. When Ruffin rebounded off

the ropes, Dick, who had greatly strengthened his legs with specialized

training, leapfrogged over the man (“few people were doing the leapfrog in

those days”) and as Dick reached the peak of his leap, he saw a most curious

thing.

“A shoe flew into the ring, which must’ve

been meant to strike Ruffin, who was the heel, and I watched it as it arched

like a rainbow and sailed over the both of us almost as if in slow-motion.” The shoe may have missed its mark, but Dickie

hadn’t as he had managed to secure the victory over his veteran opponent. His

first in-ring experience was a thrilling one and he enjoyed the hearty

congratulations he was receiving in the dressing room after the match. This was

something he could certainly get used to. But the mood was about to quickly

change.

Several men had suddenly burst into the

room carrying the body of a man that they then laid out on a nearby table. That

alone was an expected occurrence but there was something else that Dick found

odd.

“I noticed that the guy only had one shoe

on. And so I said to the boys, ‘Look, fellas, he must be the guy who threw the

shoe in the ring!’” The man on the table was dead, and while it was certainly

an unfortunate occurrence, like sharks smelling blood, the veteran wrestlers in

the dressing room also saw it as an opportunity for a rib and to break in the

rookie.

“’You killed him!’ says one of the boys,

and another one added, ‘you murderer!’” recalls Steinborn. “I began to think

that something I had done in the ring really did kill the guy. What those guys

didn’t realize was that I had the strength of my father, but the emotions of my

mother.”

Devastated, the 17 year-old-rookie

wrestler quickly grabbed his bag and headed for the train station. The train

ride home to New York felt much longer than

the ride into Baltimore

But Milo

offered words of comfort to his son and Dick was further consoled by the fact

that no one really held him responsible for the death of the one-shoed man, and

that in fact it was the combination of the man’s pre-existing ill health and

his drunkenness that night which had caused his fatal heart attack. The

following week Dick would return to Baltimore

“I’ve wrestled in 44 states and 14

different countries,” says Steinborn of the career that spanned 33 years and

included over three dozen wrestling title reigns. “Wrestling’s been my

life. It’s been a love. You can’t destroy the love of a passion that

you have.”

Genius

|

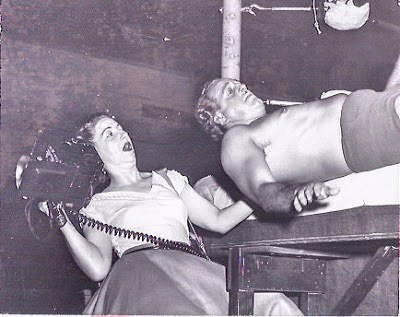

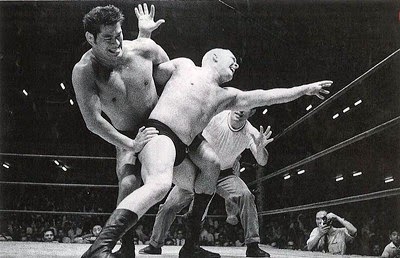

| VS. Antonio Inoki in Japan |

“One of the greatest workers I ever saw

was Dickie Steinborn in Georgia

Jody Hamilton also fondly remembers those

matches as well, citing Steinborn as his all-time favorite opponent. “We once

did a 2 hour 45 minute match with no falls and we kept the crowd!” said Hamilton

During his extensive travels as a

professional wrestler, Steinborn always remained a student of the game, despite

how much he had already come to grasp about the business. He incorporated

various styles into his ring work, adding dimension and versatility to his ring

repertoire, and he could often emulate the best moves of some of the performers

he came across.

Such was the case when he was asked in

1968 to substitute for Tim Woods as the masked Mr. Wrestling after Woods left the Georgia

territory in a dispute with the Atlanta

“It turned out that Mr. Wrestling had lost

the match,” recalls Ron Starr, who at 18 years of age at the time, was still a

fan, but would later go on to win more than 30 titles of his own as a

professional wrestler. “But when Mr.

Wrestling unmasked, it wasn’t Tim Woods, but Dickie Steinborn! I could’ve sworn

that it was the original Mr. Wrestling in the ring because Dickie worked the

match with the same exact style as Doug Gilbert, and I could not tell the

difference whatsoever. It was one of the greatest matches that I ever saw.”

“Be careful what you decide to do in life,

for you will succeed,” is one of Dick’s observations on life and a motto he

lives by. There is no doubting his

success in the ring and his ability to comprehend and use what it took to

emotionally suck the fans into what transpired in the “squared circle” was

recognized by his peers. This would lead to him booking angles in Puerto Rico

and Canada , as well as

promoting several towns in Georgia

But all work and no play make for a dull

boy, and when it came to pulling ribs or practical jokes, Dick Steinborn’s

creativity excelled in that arena as well.

“I’m Thinking of a Number…”

It was the summer of 1958 in the Houston , Texas

“I get in the car with Larry Chene,”

recalls Steinborn, “and I’m sitting in the front passenger seat and sitting

behind me is John Tolos who’d just come up from California Houston

“So I’m sitting in the restaurant with

Larry Chene and Tolos and Curry are on the other side of the restaurant and

Larry said, ‘How are you at ribbing?’ I said, ‘I love to rib.’ Larry then says,

‘Let’s tell Tolos that you’re coming in as a mentalist.’ ‘Well how the hell am

I’m going to do that?’ I asked.” Chene and Steinborn would then work out a

scheme involving the use of codes in order to successfully pull of the rib.

“So we get into the car and Larry Chene

asks me in front of the other guys, ‘So, what’s Morris bringing you in

as?’ I said ‘as a mentalist.’

“From the back seat Tolos blurts out ‘Oh,

Bullshit!’And Larry says, ‘What are you talking about?’”

“I turned around and said to Tolos who’s

in the backseat, ‘Think of a number and write it down and pass it to Bull, and

then Bull you whisper it to Larry.”

“Larry is driving with his left arm out the

open driver’s side window with his left hand gripping the bottom of the window

frame. He then starts tapping his left thumb on the door 7 times. I tell Tolos,

‘your number was 7.’ Tolos is astounded

and blurts out ‘Tre-men-dous!’So we go through the numbers thing 3 or 4 times,

and with each success Tolos would exclaim, ‘Tre-men-dous!’ says Steinborn with

a hearty laugh.

“So now I thought that I’d make it more

interesting”, continues Steinborn. “So then we did names and then I asked for

everybody’s wallets. I told them I’d be

able to tell them how much money they had in their wallets. Larry looked at me

like, ‘How the hell is he going to that???’”

Knowing how much Chene and Tolos received

for working in the semi-main event the previous night and how much Curry got

for working in the main, Steinborn used some brilliant deduction to figure how

much each had spent on food and how much was contributed to gas and was right

on the mark in guessing what each man had in his wallet. “Tre-men-dous!”

proclaimed Tolos.

A few years later Tolos and Steinborn

would catch up with each other when they’re working a card in Detroit

Tolos then looked up at Steinborn and

after several years of not seeing him, the first words to come out of John’s

mouth were “I’m thinking of a number.” Years later Tolos was still spellbound

by the “mystical” powers of Dick Steinborn.

At the End of the Tunnel

Life is not always fun and however and

Dick Steinborn would see what some might think were more than his fair share of

trials. He has been married four times

during the course of his life, the first time being when at the age of 20, he

married Carol Kerce, a beautiful young woman he had met at a roller rink in Orlando , Florida

Several years before this beautiful union,

Steinborn’s mother had given him his first camera as a present on his

fourteenth birthday, saying, “As we get older, we forget about certain things

and sometimes even what people looked like.

But when you click that shutter, you will capture and have those

memories forever.” The pictures from the time period in which Dick and Carole

got married shows two young people in the prime of their lives, deeply in love

and seemingly without a care in the world. Tragically, that would come to an

end.

At

the age of 28, Dick Steinborn would become a widower, as his beloved wife Carole

passed away from cancer. Overcome with grief, Dick Steinborn took to the bottle

in an effort to escape from his grief, taking on Florida

But the inner strength he possessed

allowed him to eventually overcome if not forget his grief and Dick Steinborn

persevered, and would continue on in life, ready to meet any challenges it

might bring. But it wasn’t always easy.

His second and third marriages would end in divorce, the third marriage ending

during a time that was already particularly difficult for Steinborn.

In 1984 Dick was involved in an auto

accident that left his spine twisted even two years after the crash. His wrestling career, which he had aspired to

ever since he could remember and had participated in for 33 years, was suddenly

over. Steinborn was devastated. It

wasn’t just a matter of a loss of his livelihood, which was bad enough, but it

was the loss of something he loved, something he excelled at. He had derived a

certain amount of self-worth from his ability to perform, create, and express

himself in the art form known as professional wrestling.

“I went into a two year depression,” he

says. “I lost my family, lost money, lost everything.” It was then that the

divorce between him and his third wife Sheila took place. “She told me that I had

nothing left,” he recalls. While Dick had felt that way at times during his

depression, he knew that we can’t believe every thought that we have, and that hope

is the last thing to die. While he had the emotions of his mother, he still had

the strength of his father. He refused to accept Sheila’s pronouncement. “I

said, ‘I still got me.’”

|

| Steinborn in 2004 at the age of 70 (Photo courtesy of Dick Steinborn) |

And so after two years, Dick Steinborn

would once again resume the exercise workouts that he had been neglecting and

received counseling to deal with his depression. Life is a story, and Steinborn

realized that no matter how bad a particular chapter might be for the main

character in the story, and as long as we keep turning the pages, there is the

opportunity for the story to change for the better.

Dick Steinborn would not only resume those

exercise workouts but go on to open his own business as a personal training

consultant, training several business professionals in the Richmond , Virginia

And he would find love again as well,

marrying for a fourth time and enjoying the companionship of his wife Hazel,

until she passed away in December of 2012. Again, it would be another trying

time for Steinborn, as it has only been a year and a half at the time of this

writing, since he has lost his wife. But he continues to keep active and

continues to keep positive. He continues to engage in the art of photography, a

passion that he cultivated since he received that first camera on his

fourteenth birthday from his beloved mother; he also continues to oil paint; he

works out three days a week in his home gym and boasts a trim 30 inch waist;

and he is working on his autobiography with his co-writer Scott Teal, owner of

the Crowbar Press publishing company.

And if the stories that Dick Steinborn has

shared with me are any indication of what we can expect from that book, it’ll

be a must have. Not just for the great, entertaining stories of which Dick has

a multitude, or for the wrestling history such a book would contain, but for

the inspiration one receives when he gets to know Dick Steinborn the man, not

just Dick Steinborn the wrestler. For Dick Steinborn is not just a man who has

survived, but a man who has thrived, and who even at the age of 80, still makes

a meaningful contribution to this world. His father said that he was always moving

and couldn’t keep still. And thankfully, despite whatever life threw at him,

Dick Steinborn always managed to eventually move forward.

He is a great example of the fact that we

are not just products of what we experience in life, but in how we ultimately

choose to respond to those experiences. As Ralph Waldo Emerson so aptly stated

many years ago, “What lies behind us and

what lies before us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us.” – RR

Sources:

Author’s conversations with Dick Steinborn, Ron Starr

“Interview with Dutch Mantell”, by Wade

Keller, PW Torch Newsletter #216, March

1, 1993

“The Assassin Interview”, by Bill Kociaba,

Kayfabe-wrestling.com

“Florida’s Great Wrestling Cities:

Orlando, and promoter Milo Steinborn, by Barry Rose, Kayfabememories.com

“Lord of the Ring”, by Karen Shugart, INSTYLE WEEKLY, June 28, 2011